Part 2: Changing the way we see the world

The climate crisis is calling into question our symbols of victory

Given that conquering Mars looks unlikely, salvation seems to involve coming back to Earth. Surviving here and now requires us to re-establish our planet’s sacred dimension, celebrate life in all its forms and recognise that the way of thinking allowing us to survive and develop until now has become ineffective and will lead to our downfall if left unchanged. Surviving means uniting, organising and getting along to find solutions. The enemy? The way we function, our fighting spirit, our wasteful tendencies, how we treat other living things, growth and uncontrolled demographics.

Climate change calls into question the symbols of victory in Western societies, which are either imitated or violently opposed by young (and not so young) people across the world. The survival of our species will be increasingly conditioned by the way we organise ourselves, by being disciplined, understanding and respecting life cycles, reducing waste and recycling. Yet, these values aren’t yet shared by the majority of the population, in particular, the ruling classes brought up to believe in the “male warrior” and monetary success.

As Alexandra d’Imperio points out, the ruling classes are terrified of losing their social status, which is symbolised by big, polluting cars – the male warrior’s Trojan horse -, iPhones, an array of high-tech machines programmed to become obsolete, polluting behaviour, branded clothing and an overabundance of food. In the meantime, the less well off tighten their belts in an attempt to appropriate these symbols of victory. Basically, “being happy means having more comfort and material possessions, being able to buy whatever you want, whenever you want and enjoying the associated social status”, explains poet, thinker and director, Cyril Dion, in relation to our current way of thinking. In order to change society, we have to tell a new story (Reporterre).

How can we transform our current way of thinking?

Which words and stories could help us explain that our chances of survival won’t improve by opting for ultra-consumption, but rather minimalism? How can we demonstrate that success lies in consuming less and learning mastering yourself?

Changing a system of anchored values

Currently, we have a framework of references linked to the past that largely fail to describe our future. To bring about change, we need new stories, value systems, social codes, models, ideas and lots of imagination. We’re desperately lacking positive, modern stories depicting a secure and desirable future for our children. Many perceive becoming a low-carbon society as a step backwards that will reduce our level of comfort and require massive investments. Yet, this projects an out-dated perspective onto the future. “The problem is that we always look at ecology in terms of constraint,” Isabelle Delannoy admits.

How can progress be synonymous with nature?

In the West, we tend to separate progress, material comfort and sophistication from nature, which is associated with an uncivilised, difficult way of life and evokes images of working long, physically tiring hours in the fields.

Until now, artists have represented this “going back to nature” in romantic, idealised terms, far removed from the norms of a society perceived as alienating, yet necessary to our survival. Sean Penn tells Christopher McCandless’ story in the movie Into the Wild, which explores the idea of looking inside yourself to find happiness and hard-earned freedom. The hero, a young university graduate with a promising future, decides to take to the road and leave everything behind. He discovers a life in harmony with nature, but also the weight of solitude. The story ends when he poisons himself with toxic berries in a beautiful, but inhospitable landscape.

Into The Wild, Sean Penn, 2008

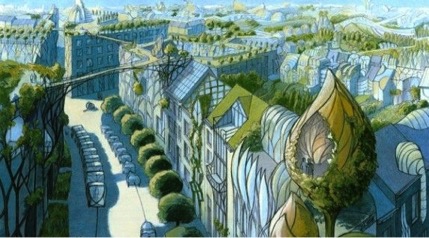

New ecological stories focus on reintegrating nature into the city. Artists and architects envisage vegetable gardens and beehives on rooftops, while engineers draw inspiration from living organisms with new and highly promising field of biomimicry. Isabelle Delannoy highlights the difficulty of introducing these new paradigms during her conferences, “in my presentations about symbiotic economy, I show images of amazing parks filled with people having fun and underneath I write ‘purification station’. This allows me to bring together notions that we don’t usually associate.”

For their part, Cyril Dion and Mélanie Laurent are looking to build an inclusive and coherent vision of the future, conveyed by modern heroes, such as Vandana Shiva, through the public format of film. Together, the pair directed Demain (Tomorrow), to shake up the collective imagination, “When we talk about ecology, it often conjures up images of idealistic shepherds in sandals looking after sheep in Larzac. With this film, we wanted to tell a different story to show that lasting solutions exist and that they can work on a large scale, like the San Francisco zero-waste policy (…) We’re talking about a completely new way of picturing the world.”

Luc Schuiten – www.thegreenrevolution.it

New words to talk about inner transformation

When I started this Storytelling and Ecology project, I wasn’t sure that we were using the right words. We were referring to “saving the climate”, when we needed to talk about “saving the future of mankind”; “climate change” when we should have been talking about “the survival of our food system”. I was convinced that we needed to change the way, and the words we used, to talk about the environment. I summed up these tips in the 10 commandments of impact journalism.

We lack words to describe the reality of a world that is caving in on itself to give rise to a very different reality. We’re using words from the past, like “socialist” and “communism”, which create confusion by evoking an out-dated vision of the world. Instead, we should be using new “virgin” words to talk about the future. The right words, such as “ecology”, have been dragged through the mud. The trouble with words like “climate change” is that they seem totally disconnected from our reality.

However, the real problem doesn’t derive from the words that prevent us from seeing reality, but from our view of the world, which is itself a prisoner of words that are unsuitable to describe our new situation. These words simply elevate an expired vision. We try to distance ourselves from a problem that is an deep, internal part of our lives, way of thinking, relationship with the Earth, values, the way we envisage our future and, therefore, also the collective stories we tell ourselves and believe to be true.

Erik M. Conway and Naomi Oreskes define the word “environment” in the glossary of archaic terms in The Collapse of Western Civilization as, “An archaic concept that, having separated human beings from the rest of the world, assigned an aesthetical, recreational and biological value to non-human components – see ‘Protection of the environment’. A distinction is sometimes made between ‘natural’ environment and ‘man-made’ environment, which, in 20th century, confused people who subsequently struggled to grasp and acknowledge the omnipresence of their impact on the world.”

Now, more than ever, we need new stories and myths to create a universe capable of inspiring the masses. We have to explore, see and experience another reality with new tales woven from language of the future. The current political class, as well as the majority of thinkers, writers, economists and philosophers, are failing to hear and convey these new stories, which rethink the relationship between man and our nourishing earth, the source of all life.

COP21 in Paris in December 2015 set into motion a new, global story in which our role is rethought, debated, renewed and restructured. These new stories filled with meaning and hope for the future are currently being created and assembled on social networks. They are starting to forge a path through Western thought patterns thanks to alternative artistic movements such as the Solar Punk Project, magazines like We Demain and initiatives such as Place to B.

(Read Part II : Mobilising our intellectual, creative and political forces)