Following Trump election in the US last November, Place to B has decided to launch a new project called “Inside Out“. Often times when actors are interior to events, both accuracy and perspective are

Following Trump election in the US last November, Place to B has decided to launch a new project called “Inside Out“. Often times when actors are interior to events, both accuracy and perspective are compromised by being too close to the action; and sadly, often the inverse also holds as well. With Inside Out, we will exit single issue focused, objective, reductive reporting and try together to create a new type of journalistic narrative that takes us beyond the binary. So – perhaps this double Inside Out, Outside In approach would be something you would like to explore with us, to create a journalistic voicing that rises above the deafening solo barrage from our current polarized liberal vs conservative reporting. We hope this interests you and you will help us to create a space for a renewed narrative; and a different, and perhaps more accurate, story.

Inside Out is edited by Sami Cheikh Moussa and Joe Ross.

Find below the next article by Mateusz Mazzini, Latin Americanist and sociologist of memory.

By looking at the recent political shakeups in Poland and Hungary, Americans can see what is to come next for them

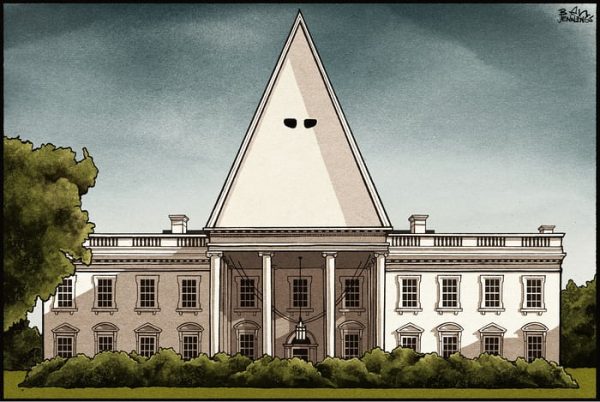

When the violent events at Charlottesville unfolded a couple of weeks ago, many members of the American public remained sat on the edge of their armchairs, glazing with shock and disbelief while watching the coverage of full-on Neo-Nazis marching with their heads up high through the local university campus. The mood of the nation was still anything but at peace, when it took another hit, this time from its own leader. Donald Trump, in a rather inexplicable manner, failed to unequivocally condemn the racist, nazism-propelled far right extremists for spreading aggression and havoc, claiming there was „violence on both sides”. And while this was nothing else than yet another attempt by Trump to normalise the renascent American extremism into the mainstream public debate, it was also a loyal reflection of policy ushered in by Poland’s Jarosław Kaczyński and Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, the two European leaders constituting the very avant-garde of anti-democratic crusade of illiberalism.

Ben Jennings on Donald Trump and Charlottesville – The Guardian

Orbàn has been governing Hungary for little over seven years now, while Kaczyński is Poland’s kingmaker, pulling strings from a safe, politically unaccountable position of party chairman and ordinary member of parliament. Both, however, share a considerable set of similarities in governance. Their disdain for democratic institutions, aversion to rule of law, disregard of the facts and deliberate exacerbation of political hate discourses are well known to the European public. Nonetheless, the recent months, especially in Poland, have brought about an instance of anti-democratic policy unseen in this country since its 1989 democratic transition, widely acclaimed to be the region’s success story in moving away from single-party socialist state.

In late July, the ruling Law and Justice party rushed through the parliament a set of three bills attempting at redesigning Poland’s justice system. Powered by claims of supposed „making up” for a soft approach to vetting of former communist servants making it into the post-transitional administration, the government wanted to virtually purge all juridical instances and replace its employees – judges, prosecutors – with their own, politically backed appointees. The bills, if passed and signed by the president in their intact, original wording, would, respectively, expire the terms of all sitting Supreme Court judges and their successors be hand-picked by the incumbent government, transfer to the parliament the oversight of the National Council of the Judiciary, a formerly independent institution in charge of appointing judges; and move control of personnel appointments in the lower courts to the justice minister.

Both the content of the bills and the hasty, controversial mode in which they were pushed through the parliament ushered in an unprecedented level of civic disobedience among Poles. For days hundred of thousands of people were gathering every evening first in front of the parliament building, objecting the violation of democratic procedure, later moving outside the presidential palace and demanding its main occupant vetoing the controversial laws. Protests went on for almost a week, spreading across the entire country and numerous other European capitals, including Berlin, Brussels and London. With the younger generation joining the mid-aged protesters for the first time since the October 2015 election, when Law and Justice won an all-out majority as the first party in Poland’s post-transitional history, the demonstrations scored a considerable success. In an unexpected turn of events, president Andrzej Duda, previously thought of as a figurehead to the government, announced a veto to two of the three bills. And although the one he allowed to pass, on the rules binding the nationwide network of courts, was maybe the most harmful one, and also considering the veto could still be overruled by the parliament, civic disobedience paid off.

Protesters in front of the presidential palace in Warsaw. JANEK SKARZYNSKI / AFP – Getty Images

Be that as it may, this instance of anti-democratic politics is by no means the most harmful act of hindering social cohesion in Poland. A deeply divided, heavily polarised society sees lines being drawn even deeper with the government’s normalisation of far-right political groupings. And in fact this is where parallels with Trump begin to be apparent. Violent white supremacist marching through cities’ main streets demanding immigrants be expelled and nation returning to racial purity? Poland has seen it all before, with the National Radical Camp (ONR) becoming a recognisable socio-political actor. Drawing on pre-war traditions of their predecessors, the ONR activists fight against marriage equality, the presence of immigrants and liberalisation of social demeanours with a tacit approval of the government. Law and Justice, just like Trump in Charlottesville, does not condemn them, but they do not fully co-opt them either. It is not worth the political risk. The cooptation in both cases is selective, depending on current needs. Law and Justice does not want to get its hands dirty on discourses that could antagonise its more moderate electorate, but a further radicalisation certainly serves their strategy. Thus they allow the neo-nazis to march and when it suits them, they echo the radical message (as in the immigration debate). In turn, when the rhetoric crosses certain boundaries, they portray themselves as „defenders of the moderate”, „protectors of mainstream”, warning that had it not been for them, the radicals would have an open highway to power. And, in fact, when left with a choice between the anti-liberal, but yet non-violent eurosceptic conservative like Kaczyński, or a group of inexperienced white supremacists, the decision seems somehow obvious.

As said before, Eastern Europe is one step ahead of America in this anti-democratic decay. What can, therefore, Washington learn from Warsaw? First of all, to protect the centre. With clever conservatives such as Kaczynski in power, the centre shrinks drastically and gravity moves further to the right. Breathing space emerges for radicals as well. Those who hitherto occupied moderate positions of reason, are now marginalised and semi-radicalism becomes the new normal, the new mainstream. Numerous established writers, such as Masha Gessen and Timothy Snyder, warned about this shift and called upon the centrists to fight back. Scrutinise the administration, fact-check the politicians and media, but most of all, call the threat by its real name and do not obey in advance.

Allowing anti-liberal bigwigs such as Kaczyński and Trump to govern undisturbed simply due to their powerful direct legitimacy acquired through elections is a first step to normalise what actually is a pathological, distorted version of democracy. No society can afford that to happen.